The blackworked half smock

The blackwork

In sixteenth century Europe, blackwork was the most fashionable and go-to style of embroidery for linens. The relatively simple materials required – linen, a contrasting fine fiber, and the ability to count threads – saw a veritable blooming of this intricate style of embroidery. Surviving examples include smocks, sleeves, coifs, forehead cloths, the occasional cushion, at least one skirt1, and many, many portraits.

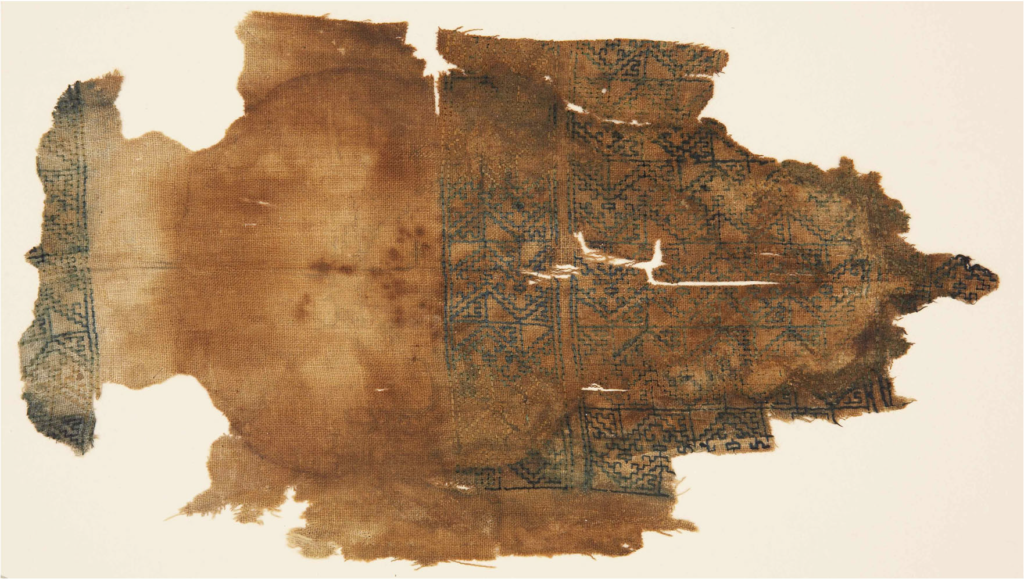

Remaining examples of early medieval designs are highly geometric. There’s a strong resemblance between blackwork and a monochrome Middle Eastern embroidery technique which may have migrated to Europe from Egypt via Moorish Spain.

The example below is 13th-15th century, from Egypt2.

It was once thought that blackwork came to England with Catherine of Aragon, who arrived there in 1501. However, it was in use much earlier. One of the earliest literary appearances of blackwork can be found in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, written between 1387 and 1400. His description of the miller’s wife’s smock sounds like the classic double running stitch used in blackwork, where the pattern is the same on both sides3 :

Of white, too, was the dainty smock she wore, embroidered at the collar all about with coalblack silk, alike within and out.

Blackwork evolved rapidly to include a wide range of patterns; from intricate geometric repeats to an almost freeform style, lively with critters and fanciful flora.

Like the collar of the miller’s wife’s smock, the geometric motifs are sometimes reversible. A double running stitch and thread counting can permit the pattern to be the same on both sides. This method of blackwork embroidery is also known as Holbein stitch4 because of its frequent appearance in his portraits. It’s one of the few kinds of embroidery that follows the (totally unrealistic) Victorian conceit that embroidery should be as tidy on the back as on the front!

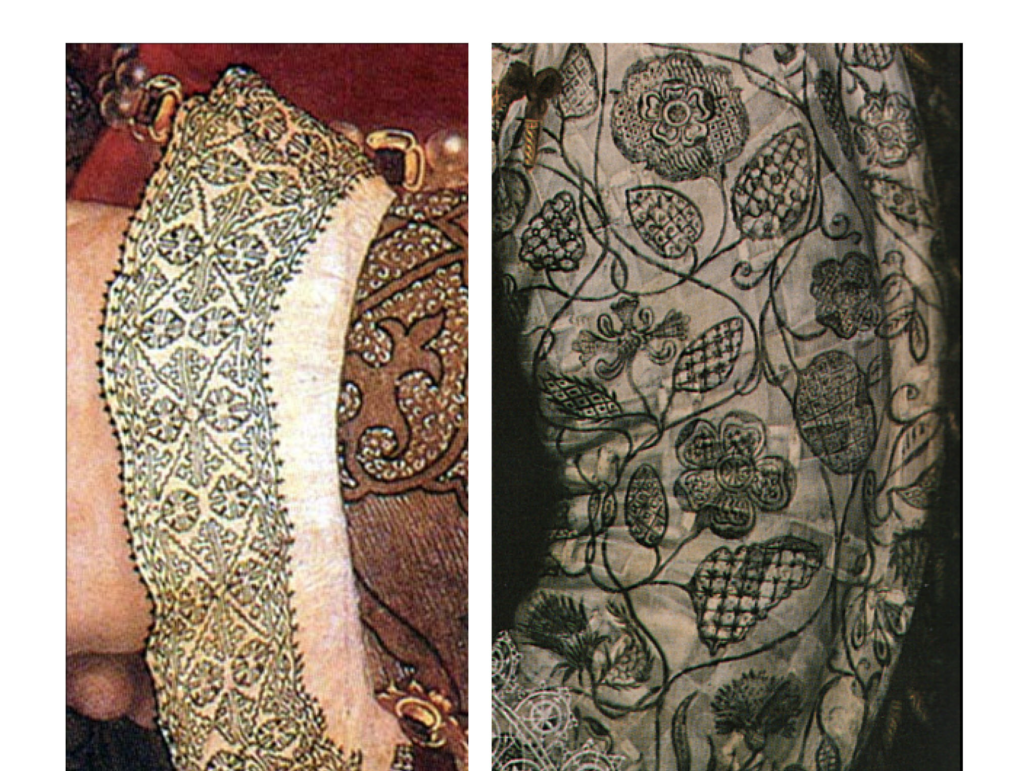

The cuff on the left in the image below5 is from the 1530 Holbein portrait of Jane Seymour. The embroidery painstakingly painted illustrates counted stitch blackwork being used to produce an intricate and delicate geometric pattern.

On the right is the slightly later portrait of Queen Elizabeth’s sleeve (from an unknown artist in 1590). Compared to the cuff, the sleeve demonstrates the evolution of blackwork from the early geometric style to the later freeform style.

The design

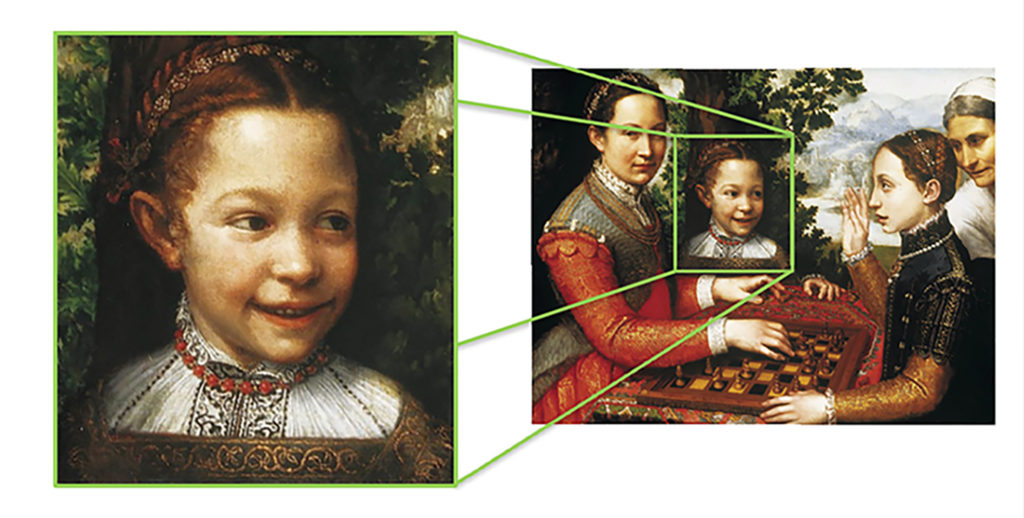

The collar, plackets, and cuffs of my linen waist smock are embroidered in the later, freeform style. The design was inspired by the front panels of the smock worn by Europa Anguissola in her sister Sofonisba’s painting The Chess Game6:

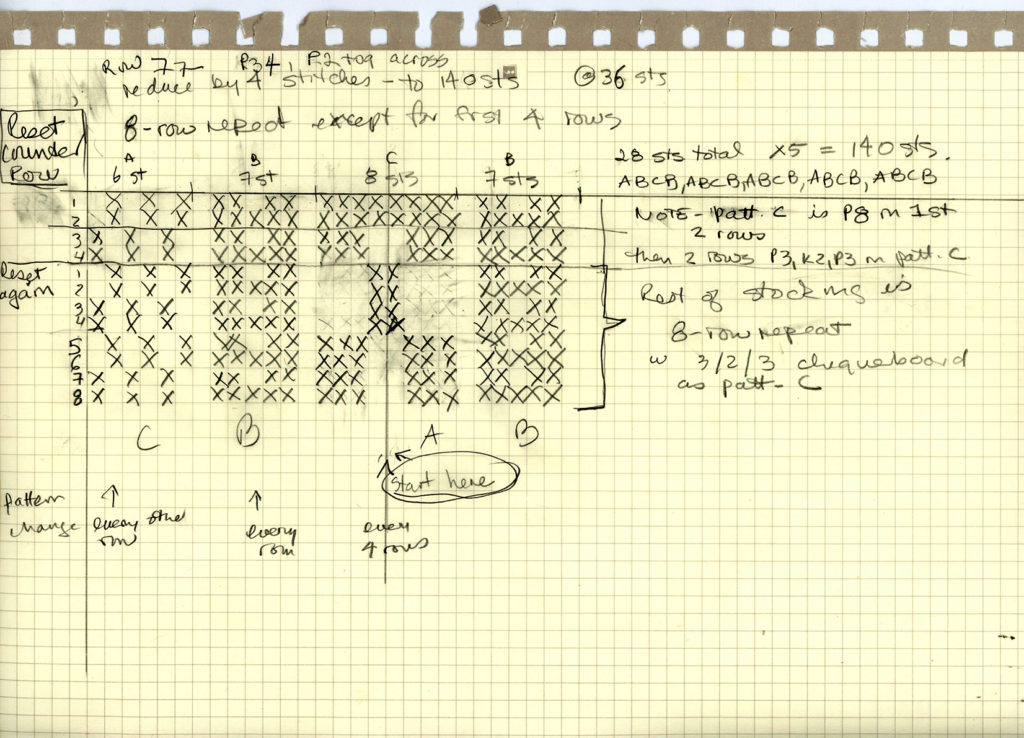

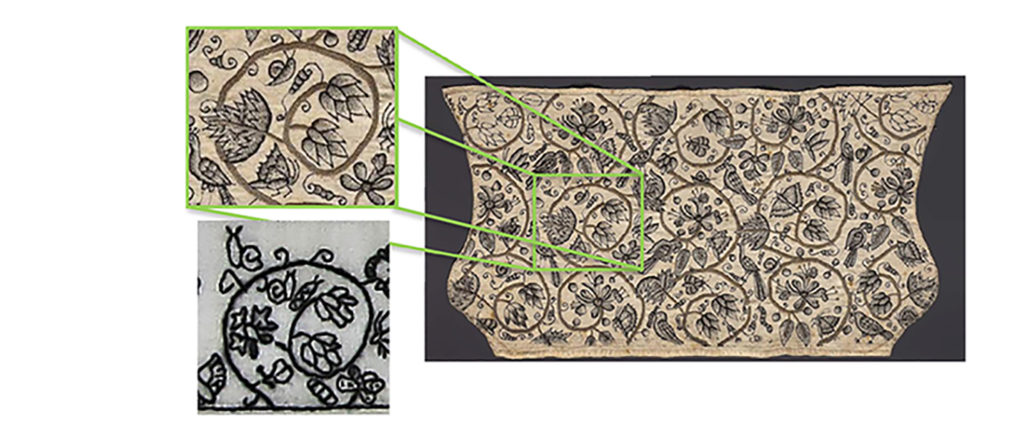

The motifs are an adaptation of those on this coif in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston7:

I adapted the design, adjusted the scale, redrew it, and added pea pods & snails for whimsy.

The finishing trim and ties are an adaptation in black of the crisp whipstitched cord edging and ties on the collar of this shirt from the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, which I also used as a model for the cut. I have used the rectangular cut8 of a shirt because, as the half smock only goes to the waist, it doesn’t need the hip width provided by the triangular gores that are used in women’s full-length smocks. The shirt is also shown in the well-loved Janet Arnold tome: Patterns of Fashion 4.9

For my half smock, the ground fabric is white handkerchief linen, and the thread is loosely-twisted black filament silk. The embroidery is mostly executed in stem stitch, with a sprinkling of others – such as spiderweb, stippling, blanket stitch, and herringbone – where the motif suggests it.

Assembly

For the main seams, the individual pieces are hemmed and assembled with a faggoting stitch. The other seams are clean-finished using whip stitch, slip stitch, or flat felled, where appropriate.

The strings at the neck and cuffs are fingerloop braided from buttonhole-weight spun silk. To keep the front panels in line, I made a hook and sewed it in below the placket. It’s made of 18 gauge brass wire, formed with pliers, and work hardened in a tumbler. It fastens with a thread loop, which is less likely to unhook than a matching metal one would be.

Comments Regarding Blackwork and The Internet

Today, April 13th, 2022, searching for “blackwork embroidery” on the web brought up 2,780,000 hits. I included “embroidery” in the search terms because just “blackwork” brings up a lot of tattoo pages, which are sometimes interesting, but usually irrelevant. Many of the “embroidery” pages are also irrelevant to research: touting clothing, commercial embroidery services, supply sales, kits etc. However, if you have the patience to wade through the distractions, there is a lot of good, solid information and research out there. A very deep rabbit hole – easy to lose an afternoon in.

- The Museum of London, accession # 59.77b. [↩]

- Textile Museum of Canada, accession # T88.0029, retrieved from https://collections.textilemuseum.ca/collection/4957/ [↩]

- The Canterbury Tales, 1435, Duke Classics, eBook, ISBN 978-1-62013-113-8, P. 324 [↩]

- Eaton, Jan. Mary Thomas’s Dictionary of Embroidery Stitches, Revised by Jan Eaton. London: Hodder&Stoughton, 1989. ISBN 0-340-51075-7 [↩]

- Image from Wikimedia Commons; supplied by By PKM – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5793298 [↩]

- Image from Wikimedia Commons; supplied by the National Museum in Poznań, https //en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Game_of_Chess_(Sofonisba_Anguissola) [↩]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Accession Number 1996.51 [↩]

- Victoria and Albert Museum, Accession Number T.112-1972 [↩]

- Arnold, Janet et. al., Patterns of Fashion 4 c. 1540-1660, The cut and construction of linen shirts, smocks, neckwear, headwear and accessories for men and women, Macmillan, London, ISBN 878-0-333-57082-1, 2008, p. 17 [↩]